From Barcelona to Barcelona. How Alex Ferguson and his civil servants learnt Europe

Looking back on the 1999 Champions League final, Alex Ferguson remarked, ‘the celebrations begun by that goal will never really stop’. ‘That night in Barcelona’ was about far more than one period of stoppage time. And more than one night in Barcelona. The road to Camp Nou was littered with failure, mistakes, regret, disappointment, and learning. When Ferguson told his players at half time in the final, to ‘just make sure you give it your all, because at the end of the game you’ll have to walk past that trophy and you won’t be able to touch it,’ this spoke deeply of a man who had been enthralled by European football since watching Real Madrid enchant his home city of Glasgow as a teenager. Being present in the crowd at Hampden Park as a teenager, while Di Stefano and Puskas despatched Eintracht Frankfurt 7-3 in the 1960 European cup final, sparked a life long obsession, calling for Ferguson to touch his ‘holy grail’ of the European Cup trophy. Ferguson noted as he attended the 1997 European Cup final in Munich, ‘just to rub it in…the European Cup itself is displayed almost exactly in front of me. I can’t take my eyes off of it.’ Two years later he would get his wish.

It is difficult to overstate the sense in which the spectre of the European Cup hung over Manchester United in the 1990s. In July 1994 Ferguson stated, ‘the European Cup was the only blot on our great record last season…even though it is only a month away it is still exciting. The European Cup is the great challenge,’ and again in May 1996 ‘I shall make it clear to everyone…we are determined and ready to make our mark in Europe.’ In these years there is an almost child like enthusiasm in the awe Ferguson beholds Europe. He marvels that, ‘Barcelona’s organisation is absolutely magnificent. It is a big club operating in exactly the right way.’ Ferguson clearly sees European competition as an academic exercise he was desperate to master, citing ‘the variation in Europe, the way danger can suddenly hit you out of nowhere…has always intrigued me.’ He confides in his diaries ‘that is how I judge myself. If I look at my career, I would say ‘what did I do in Europe?...So I’ve got to stretch myself, the players and the club to the maximum.’ There is also a slight sense of insecurity, Ferguson delights at interacting with the big names of European football in a way he never does with his British counterparts, seemingly in awe at managing ‘a few words with…Marcello Lippi [as he]…took a puff of his big cigar…Europe was our big challenge now.’ Indeed in sharp contrast to his domestic rivals, Ferguson states, ‘I have too much respect for…Marcello Lippi and his team to make it such a personal confrontation’. Ferguson is almost giddy at the challenge, stating, ‘The great thing about European football is that it seems to extend your life. I always seem to go to bed later after European matches because of the adrenaline rush they give me.’ In his darkest moments Ferguson, ‘start[s] to question the European scene. Is it really an ogre? Is it such a big bad wolf that we can’t handle it?’ Ferguson’s players certainly conformed to his message, Roy Keane stating, ‘success in Europe was of course the number one challenge,’ Gary Neville describing ‘the task loomed as high as Mount Everest’. Peter Schmeichel reveals, ‘I burned to win the Champions League…my reference point for success.’

As Ferguson feared however, there were plenty of reasons to see Europe as an ogre. Schmeichel states, the clubs’, ‘European resume…was just a document of disasters.’ It is worth noting the scale of the task the club faced, as United embarked on their first European Cup campaign. In 1993 the English league coefficient strength ranking languished in 9th place. For a contextual comparison, as of 2021 the country occupying 9th place in these rankings is Belgium. Even in 1998 as United begun their historic treble season, the English league was rated as the 6th best in Europe. In the aftermath of the 5 year ban from European competition for English clubs following the Heysel disaster in 1985, English football was isolated and had fallen far behind its European counterparts to the extent it could be viewed as largely a provincial affair. As the 1990s progressed, aging or unwanted continental European forwards could revitalise their career simply by going to the Premier league and confounding defenders by dropping off into a number ten position, as Nandor Hidegkuti had for Hungary at Wembley as far back as 1953. English football had quickly regressed. In this context United really were attempting to scale Mount Everest in trying to compete with the best Europe had to offer. Ferguson is dismissive of his English contemporaries’ efforts in Europe, ‘Blackburn rely on forcing errors…but I don’t think you can do that in Europe. You’ve got to probe and create, be patient, work the ball around, but Blackburn were just knocking it forward.’ More generally stating, ‘the thing about the English game is that it is so open and free of calculation…we don’t have a tactical game in England…we give the ball away and get it back quickly. There is no great concentration on keeping the ball. But you go into Europe and give the ball away and you can’t get it back.’ Roy Keane lamented, ‘the European game was much more sophisticated and punishing than the Premier League. In domestic league football you could afford to be sloppy in attack-where, if you gave possession away, you’d quickly regain it-and in defence where mistakes were not, as in Europe severely punished.’

As Premier League champions in 92/93 Manchester United entered the Champions league. After beating Honved of Hungary, United faced a two legged knock out against Galatasaray to decide who would compete in the group stages. Ferguson stating after losing this tie, ‘our sufferings was self inflicted.’ United quickly went into a two goal home leg lead, before they ‘replaced controlled aggression with self indulgence. Players started to run with the ball and to make a habit of losing it.’ United ended up gifting Galatasaray three away goals in a 3-3 draw at Old Trafford, before exiting the competition after a nil-nil in the infamous ‘welcome to hell’ game in Turkey, where Gary Pallister recalls a hotel worker looked at him and ‘ran his finger across his throat.’ As Roy Keane outlines, ‘at the end all hell broke loose’. Eric Cantona was sent off for an altercation with the opposition goalkeeper and later attempted to fight a policeman who had hit him with a truncheon.

The 93/94 era team is as beloved as any in Manchester United’s history, Ferguson himself describing them as, ‘one of the very best teams ever to wear the United colours…I have no doubt that they would stand up well to any comparison. Even after the dazzling treble triumph of 1999 I cannot say categorically that [they]…are superior to their predecessors of five years ago.’ However, the indiscipline as seen in the Galatasaray tie can be seen as a design feature. Ferguson noted, ‘one obvious difference is that the first double winners presented me with far more problems as a result of outbreaks of indiscipline on the field.’ The ‘fundamental qualities’ of that team were ‘in addition to outstanding skills…physical strength, courage, toughness of mind, speed, power and determination. They were winners and in quite a number of cases the other side of that coin was that they were bad losers.’ While Ferguson did ‘cherish’ the ‘combustible drive’, he does accept, ‘when they were massed together the aggressive tendencies could get out of hand.’ Ryan Giggs recognises the benefits of such drive, noting ‘the fighting spirit could serve us well but it could also be our undoing.’ Roy Keane described this as a ‘team of men’, lifestyle wise, ‘these men knew how to play…Ferguson and Kidd had no problem with the idea of players having a few drinks.’ Keane further outlined, ‘a serious drinking subculture…Ferguson and Kidd…weren’t running a boy scouts brigade. Boy scouts don’t win trophies.’ Lee Sharpe concurs, ‘It is also wrong to say Alex Ferguson completely disapproved…drinking was part of English football.’ Interestingly Sharpe feels like Ferguson, ‘was able to understand it…it was a genuine, old fashioned, working class drink problem, and that he could relate to. I don’t think it ever made him question…attitudes if he was in a backstreet Irish pub all day. ‘ At the time, ‘Robbo (Bryan Robson) was still organising sessions out for the lads…it was an important part of the club, for the players to bond…he used to tell the manager we were going out for the day.’ Ferguson was much closer in age and culture to the 93/94 team than to later sides and perhaps this meant he operated a different level of control than he would later enjoy as he became more detached. While this was typical of English football at the time, and there is little direct suggestion than the on or off the field indiscipline had any major factor in the teams struggles in Europe, given the level of discipline, control and dedication the opposition were operating at, would this team of men have to curb some of those impulses?

If 93/94 had left some doubts about United’s limitations at the highest level, the following season, 94/95 was to cruelly expose how far behind the continental elite they remained. United were drawn in a group with IFK Gotenborg, Barcelona and Galatasary. United started particularly afflicted. Following his sending off against Galatasaray, Eric Cantona was suspended for the first 4 games of the campaign, and they also had to contend with the three-foreigner rule, in place until 1995, which had an oversized impact on a team reliant upon Irish and Welsh players. Nevertheless, Ferguson started the campaign in a confident mood, in trying to persuade Dion Dublin who was on the verge of joining Coventry, to stay at the club, Ferguson remarked, ‘but you may get a European medal this year.’ Indeed, United started promisingly, dispatching Gotenborg 4-2 at Old Trafford in typical style. Ferguson did note afterwards the ‘suicidal streak in the team’, which made it ‘impossible’ to control games. Next up was a credible away draw in Istanbul, before a double header against Barcelona which would define their season, and this entire era for this iteration of United in Europe. Before the home leg Ferguson warned his players to be vigilant, stating ‘you think you are doing well and then the roof falls in a right on top of you,’ a point Ferguson ‘repeatedly make[s].’ Players need ‘total concentration and discipline, ‘they can have easy possession, they build up very slowly, and then all of a sudden in the last third they increase the pace, and it catches you’. The game at Old Trafford, a 2-2 draw, was a minor triumph, Ferguson describing the match as ‘one of the most exciting I’ve ever been involved in’, while again lamenting the fact that ‘the team relaxed for a moment. Will they ever learn?’ But overall seeing it as ‘an uplifting occasion.’ Then came the other night at the Camp Nou. Barcelona tore into a United team who were without a ’fuming’ Peter Schmeichel, as Ferguson attempted to juggle the three foreigner requirements. Schmeichel feels that this decision was maybe rooted in Ferguson’s insecurity about Europe, ‘I believe he got himself into a tangle. He was impatient for Europe to see how good he was.’ As Ferguson watched the roof fall in on his team in a 4-0 defeat, he again wondered of his team, ‘how much they really listen…we were all over the place…and they just don’t understand.’ Ferguson lamented, ‘there has to be better tactical discipline….they need to listen…they can’t just play their own game, because their own game isn’t good enough.’ Their next game was away to Gotenburg where at 1-1, Ferguson notes United went ‘completely gung-ho and lose two goals to counter attack’, while ‘Paul Ince was sent off for dissent’. Manchester United were out of Europe. Ferguson describes this as ‘sharpen[ing] your appetite for trying again and most of us were desperate to have a crack at winning the greatest prize in club football.’ Something had to change.

The revolution enacted by Ferguson in the summer of 1995 is commonly ascribed to the recognition of an outstanding crop of young players developing, Ferguson merely had to make room for these players. However, while Alan Hansen famously stated, ‘you can’t win anything with kids’, what if the opposite was true for Ferguson? That he couldn’t win what he wanted to win with ‘men’. Ferguson had created a team that could dominate in England, but was unable to put in place what was needed to compete in Europe. The team was steeped in English football tradition and set in its ways, whether that be regular drinking sessions, a raking tackle or failure to keep possession and defensive discipline. Ferguson’s diaries for the 94/95 season are full of references to his players failure to listen to him or follow instructions. ‘That attitude that you can give the ball away and get it back within minutes is an indictment really. It doesn’t apply in Europe: there it is a death sentence. ‘ The team Ferguson had built had achieved great success doing things their way and had trouble adapting to a new way of playing. As Ferguson stated in November of 1994, ‘the problem with United is that a lot of them have their own profile and want to play their own way, it doesn’t work in Europe as we have discovered…I tended to get more benefit from doing tactical things at Aberdeen than I do now, because they were a young side and would listen.’ Paul Ince, who had taken to calling himself ‘the guv’nor’ and was sold in the summer of 1995, comes in for particular criticism in this regard. ‘Paul is a tremendous player and probably is the best midfield player in England, but it is just a different game in Europe.’ Ferguson expanded on his decision to sell Ince, ‘he had worried me with his altered approach to the game. He was spending more and more time going forward but not coming back quickly enough and it was quite apparent that he was getting completely carried away.’ After a defeat against Liverpool in March of 1995 Ferguson lamented, ‘players really need to listen to what we are trying to achieve tactically…and we decided Paul Ince should play more on the left hand side….But Paul kept drifting to the right…if Ince had stayed to the left hand side and disciplined himself we wouldn’t have had any problems at all.’ This is in contrast to Roy Keane who ‘can do anything you ask him to do because he has quite a disciplined mind.’ Peter Schmeichel feels that Ferguson, ‘did not want a set of mini guv’nors emerging from our reserves thinking it was all about them and not the team.’

Ferguson was particularly taken by the idea that ‘you’ve definitely got to play man for man in Europe. I think you’ve definitely got to get against opponents individually.’ One of his big tactical innovations was to drop Steve Bruce for the home game against Barcelona in 1994 to enable United to, ‘go one on one against Romario and I’ve chosen Paul Parker. He has pace and is the best man marker in English football.’ What is striking is Gary Pallister’s admission that as kick off approached in that game, he ‘took my life into my own hands by countermanding the gaffers orders. I had a word with Parks, and told him NOT to remain with Romario, but to adopt our usual method.’ Sure enough Romario escaped the defence to equalise for Barcelona and the experiment was abandoned for the return leg, in which United shipped 4 goals. A reversal Ferguson regretted, ‘if Parker had played centre back tonight it might have been a different story. It’s nothing to do with Brucey or Pallister, they are great players in our game, but we are talking about the best striker in world football, who can torture anyone. Parker is the best player in our country at handling that type of player. So what you have done is eliminate the best player on the other team. If we had done that, I don’t think we would have lost.’

United’s famed wing play was also something that may have impeded Ferguson’s efforts to introduce a more solid, possession-based game. United’s default approach was a 4-4-2 with Giggs and Kanchelskisis as outright wingers. Ferguson notes his concern at Giggs, ‘running at them right away…make sure you are passing it into the park and get hold of it in there,’ noting that ‘Ryan still has to learn.’ Ferguson felt after the Gothenburg loss, ‘there are several differences in Europe. They’re experienced and somewhere or other they try and get an extra man in….we’d say, make sure that the midfield comes in so you make up four very quickly.’ While Kanchelskisis departure in the summer of 1995 is shrouded in other factors, by jettisoning an individualistic out and out winger, structurally this went some way towards mirroring a European style. Phillipe Auclair notes that the formation that, ‘could indeed be described as a 4-2-4…more often than not when faced with continental defences more adept at keeping their shape…United’s coil would fail to spring.’ Andy Cole was also signed in 1995, as Ferguson states, ‘he makes great little runs in the penalty area. I think he is European material.’

Of course, the emblematic and iconic United player of this era was Eric Cantona. While Cantona was able to light up the Premier League, his record in Europe was more mixed. Roy Keane states, ‘Eric struggled in Europe…as I’ve acknowledged, he was superb in the domestic game, perfect for English football where his poise and technical brilliance meant he was always one step ahead of the chaos around him…Eric’s sang froid was a major asset. And because we were so strong around the rest of the park we could indulge him, spare him the chasing back, the graft, the tackling…Europe was another game, far more demanding…against the Brondbys you could get away with Eric. But not facing Juventus, Dortmund or an unexceptional, but professional side like Gotenburg.’ Going on to state, ‘I can’t recall one important European game that he turned up for us.’ Due to Cantona’s brilliance he was indulged by Ferguson, as Gary Pallister stated, ‘if Eric was doing it, then probably the Gaffer would let him get on with it,’ talking of, ‘many ways in which he was treated differently to the other players, not that any of us minded in the least.’ ’Peter Schmeichel feels, ‘in Eric’s mind I don’t think he was ever a footballer anyway. The way he saw it, football was just a station on the way to what he truly wanted to be: a figure in the arts.’ Cantona’s biographer Phillipe Auclair, describes Cantona’s frustration at not being an artist, but ‘a mere ball kicker’, he couldn’t return to the freedom of childhood but, ‘playing brought him as close as he could be to the unattainable aim…an eternal child doomed to age.’ In this vein, Teddy Sheringham recalls Alex Ferguson explaining to him the need to be more disciplined, ‘I should not go too deep to seek out the ball. He’d had a problem with Eric Cantona…Cantona sometimes came into deeper positions than he would have liked.’ As such Cantona’s ‘belief in the primacy of self-expression on the football field’, led to disdain for those such as, French international teammate Didier Deschamps, who Cantona felt, as Auclair describes, ‘revelled in the functionality of his own role…that he was an apparatchik, a civil servant’, or as Cantona famously named him, a ‘porteur d’eau’, (water carrier). However, in the grown up world of European football, it was Deschamps club team, Juventus who held primacy. Zinedine Zidane explained, ‘I understood what it meant to work for something…before I arrived in Italy, football was a job, sure, but most of all it was about enjoying myself. After I arrived in Turin, the desire to win took over.’ As Ferguson marvelled, ‘what strikes me is the attitude of the Juventus players. Every one of them works his tail off. It gives you an idea of how the power base has changed in the last ten or 15 years…the Italians analysed our game and added our strengths to their own technical ability, thoroughness of preparation and organisation.’ Roy Keane expands, ‘it’s not just the real quality players that captured everyone’s attention…but tough, wily defenders, guys nobody has ever heard of, who closed down space, timed their tackles to perfection, were instinctively in the right cover positions and read the game perfectly.’ As Lippi himself said, ‘here we never stop…no prima donnas, no privileges…if a player doesn’t agree with that he can walk.’ As ever with Cantona, there is a level of complexity and even contradiction. Cantona also stated that, ‘the team makes the individual…it’s an exchange. You need a lot of personality to accept putting yourself at the service of someone else. The creator doesn’t exist without this tactic agreement.’ Cantona certainly didn’t encourage a culture of complacency or disparage hard work. It is often stated that it was Cantona with his insatiable work ethic in honing his craft, who cultivated a culture of additional training at United. Auclair cites an example, ‘Alex Ferguson…found Cantona standing by the tactics board explaining passages of play to an awestruck David Beckham and Gary Neville, two of the players who now stayed behind to train with Eric long after they were supposed to leave. ‘

The generation of young players coming through that was to dominate the next stage of United’s development was schooled, not by the norms and assumptions of English football, but by Ferguson himself to provide the civil servants United needed to compete with Juventus. As the opening day of 95/96 season approached, Ferguson was ready to unleash, ‘another group of remarkable young players.’ Lee Sharpe notes how Ferguson was keen to develop, ‘youngsters he could mould in his ways; clean cut, dedicated, athletic, disciplined, their heads full of United.’ Gary Neville describes the youth team’s ‘intensity was incredible…we had a relentless will to succeed…there’s no doubt we had an unbelievable work ethic…an extraordinary group in our eagerness to practice.’ Sharpe remembers noticing Neville ‘practicing long throws, Gary Neville’s idea of fun.’ In true civil servant style, Neville’s nickname was, ‘busy…they thought I was trying to become the teachers pet.’ Neville was ‘willing to ditch everything else in his life apart from football and family…I decided ruthlessly I was going to make friends with my new teammates who shared the same goals as me…going out to bars…well it sounded like fun, but I didn’t see how I was going to have fun and play for United.’ As Sharpe remembers, ‘Ferguson did try and steer the young players away from [drinking].’ Sharpe himself, who is only two years older than Ryan Giggs, seems to feel caught up between the older generation, for whom drinking culture was tolerated and the younger generation where, ‘Ferguson wanted young men who didn’t get up to that sort of thing, who ate, drank, slept football with no other interests or sides to them.’ Roy Keane noted that by 1997, ‘the old drinking culture which had been the bonding mechanism when I first joined United was much less evident now.’ Whether this was a change in general football culture, (although the existence of their contemporaries at Liverpool, dubbed, the ‘spice boys’ would seem to contradict this idea), the individual personalities involved or a specific focus of Ferguson and his staff by accident or design, the generational change certainly brought about a different type of focus and professionalism.

Neville disputes the conventional narrative that it was Cantona who introduced extra training to United for the young players, ‘among the first team that was true, as a group we were doing this religiously at sixteen.’ Many of the ‘class of 92’ cite another Eric, youth team coach Eric Harrison as a vital part of this development. Neville explained, ‘Eric took boys and made us into men. He made us better footballers and, just as importantly made sure we would compete.’ David Beckham states, ‘there was never any chance of us not working with Eric Harrison in charge…if I think about the people who have shaped my career…it’ll also mean Eric…credit goes to him for turning us into footballers.’ Lee Sharpe, who left United in 1996, described it as, ‘unfortunate that I missed out on an apprenticeship with him, because he was a good coach, drilling good habits into the lads.’ It is striking how in echoes of Cantona, Sharpe describes himself as ‘a footballer, not a welder.’ The generation of players ready for the first team had been perfectly developed to act as Ferguson’s civil servants and compete in Europe. As David Beckham states, ‘it’s a bit like learning football all over again, getting to grips with the playing the best teams in Europe.’ Now Ferguson had a team willing and able to learn and listen.

It is certainly not to say the 93/94 team did not have positive benefits upon the 99 team. Peter Schmeichel who played in both teams stated, ‘without 93 there would have been no 99.’ Neville states ‘as we moved into the senior ranks, we saw competitiveness in a whole new dimension.’ For Beckham, ‘the senior players kept us going.’ Schmeichel is specific in talking of what he called ‘risk mode’, which had, ‘become our routine in 1999.’ In risk mode, United, ‘would invest everything to get back into the game.’ The 1999 team were far from a team of bloodless professionalism. As Ferguson felt Juventus had taken the best aspects of English football and added their own preparation and tactical sophistication, so had United’s 99 team to the 94 team. A strong example of this is within Roy Keane himself. Lee Sharpe outlines that, Keane, ‘made the decision somewhere deep inside himself that he was going to sack the drink, the going out, the life he led really and burrow deep into himself as the obsessive footballer.’ Keane cites the change in him to the injury he sustained in the 97/98 season, after which ‘I now cherished every moment of my football…I decided to bury Roy the playboy…only one thing counted in football: winning, actually achieving. For that I was hungrier than I’d ever been.’ Football wise, Keane looks back on matches from before and felt, ‘my distribution of the ball lacked subtlety and imagination.’ He goes on to state, ‘our style of play was geared to the English game…the European game was much more sophisticated’, and notes ‘bad habits, acquired week in, week out, as we began to dominate domestic competitions.’

Progress from this point was far from serene. However, in United’s first Champions League campaign after the revolution of 1995 they did appear more of a serious European team. The team got as far as the semi-finals in the 1996/97 season. Nevertheless, there was work to be done. In September 1996 United, met the spectre of Marcello Lippi’s Juventus for the first time and were beaten 1-0. As Ferguson states, ‘the young players suffered…the young players know what is expected of them now and I know they won’t let us down again.’ Gary Neville was less circumspect, ‘it was the biggest battering I’ve ever had on a football pitch. They took us to school, boys against men.’ Ferguson was to be proved right, as a year later, in what Ferguson described as ‘one of the great nights of European football at Old Trafford,’ in a display of ‘maturity, patience, discipline and tactical awareness,’ United were to triumph 3-2 over Juventus. This was a team who could learn, as Ryan Giggs put it, ‘it took a couple of years before we could make legitimate claims to be of similar standard,’ but claims were in process. Andy Cole ‘loved the challenge’ Juventus posed, and ‘tried to learn every time I went up against them. Talk about eye opening.’ In 96/97 United exited at the semi final stage to Borussia Dortmund with two 1-0 losses, after in Ryan Giggs words, ‘missing enough chances to have won four matches’, in what Ferguson described as a ‘devastating blow…I just don’t know how long it will take me to get over it.’ In the midst of ‘an air of depression,’ Eric Cantona announced his retirement from football. In 97/98 following the Juventus victory, United would only make it as far as the quarter finals, after being shocked by an early David Trezequet goal away goal at Old Trafford against Monaco which they never really recovered from. Gary Neville states, ‘we were a young, inconsistent side, still exploring our potential.’

In the ‘early summer of 1998…[Ferguson] decided that I had to assert myself on the need for Manchester United to spend money in the transfer market…we had gone thirty years without winning the European Cup and the domestic trophies…could not compensate fully for that omission.’ Jaap Stam arrived, who as Schmeichel states, ‘added speed to our backline,’ which enabled him to defend one on one against the best strikers. Alongside Dwight Yorke, who in Ryan Giggs words, ‘had a bit of everything…the main thing was that he could turn his man on the edge of the penalty box and dribble past, which in Europe in mind was the extra dimension the gaffer was looking for.’ Jesper Blomquist also arrived to add depth to midfield. Roy Keane sees this as a vital addition, ‘you can’t fuck around against Southampton and turn the tap on against a proper team four days later...we had enjoyed so much domestic success at this point, eased through so many Premier League games that it was hurting us when the real prize-the Champions League-was at issue.’ With these signings, ‘complacency was less likely to set in. Nobody was certain of their place.’

One game in particular stands out in the 98/99 success as representing United’s kids’ graduation in Europe. Prior to the quarter final against Inter Milan, Ferguson noted, ‘Inter’s game plan was geared to counter attacking through the middle of the opposition. That meant our full backs had to go and play in front of our central defenders, where the Italians operated with two attackers withdrawn into positions behind their main striker.’ Ryan Giggs remembers , ‘the gaffer now says this was the biggest step forward the team had taken under his management…the tie became a real test of our discipline and composure.’ Gary Neville states, ‘tactically we were becoming so much more aware as a team, and as an individual I was feeling right in top of my game. The match at Inter was a night where I felt total confidence in my ability…you feel completely in control.’

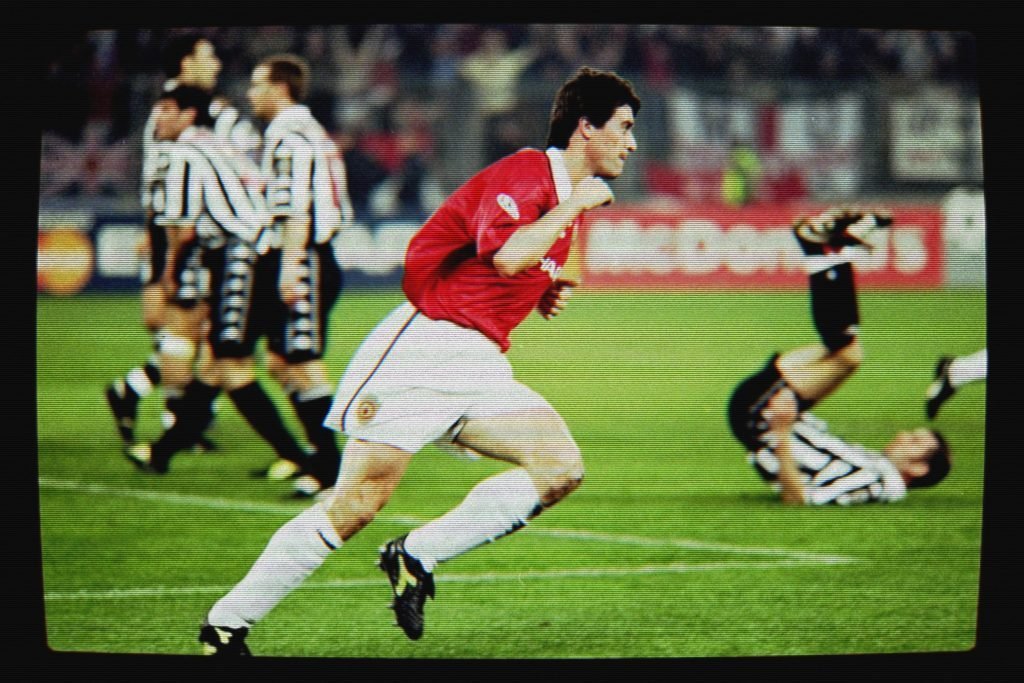

‘Can Manchester United score? They always score!’ Clive Tyldesley, 26th May 1999

‘We deserved it…this was the culmination of all the hard work since we were kids, all the toil by the manager; the result of years of learning and improving and sometimes failing. We’d sweated hard for it.’ Gary Neville

In May 1999, after winning the European Cup final in Barcelona, Alex Ferguson would finally be able to touch the trophy that had enthralled him for 39 years. While 1999 is famous for last gasp goals and excitement, it represented the culmination of years of painstaking work and far-sighted, single-minded planning. 1999 was as much a triumph of the quiet unseen work of the civil servants as it was of the drama and the artists.